Anyone who walks London knows the horrible discomfort when you can’t find a toilet. In these situations, it becomes difficult to throw yourself into a psychogeographic dérive or to ponder Charles Booth’s social geography. Fully engaged historical walking requires a level of concentration which a saturated bladder precludes, so readily available public toilets are essential for London walkers. It is, however, quite amazing how unforgiving London can be in this regard. This is especially true when you don’t want to buy a quick coffee or cheeseburger (although branches of McDonald’s are widely appreciated as de facto public toilets). The inevitability of this problem has led me to ponder the history of London’s public toilets on almost all of my walks. How did they come about? Why are so many closed? Why aren’t new ones being built? In light of this, I thought it would be interesting to shift the public toilet from the periphery to the centre of a walk, considering the social and cultural dimensions of them from the nineteenth century to the present.

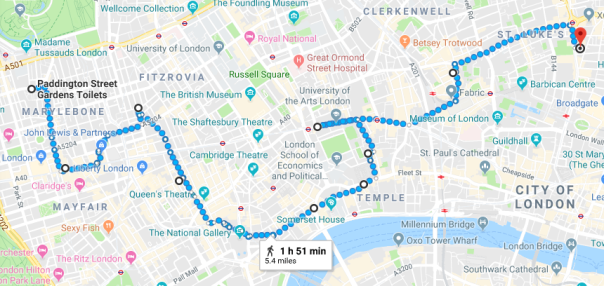

I decided to walk from one fairly arbitrary point to another: from Paddington Street Gardens near Baker Street to London’s oldest working public toilet at Wesley’s Chapel near Old Street. Between these, I decided to research a few points of interest, while keeping a keen eye out for anything unexpected.

I hadn’t been out of Baker Street station for more than a minute before seeing a convenience I wasn’t previously aware of. Although old, this has clearly been renovated relatively recently, and as such, it costs 50p to use (a contrast with its Victorian forebears). While taking photographs with a small digital camera, it suddenly struck me that my activities were drawing a few funny glances… I started to feel a heavy sense of dread at how challenging this walk was going to be. My theoretical subversions were physically manifest for everyone to see; I was giving too much attention to something that ought not to be given it, and I was feeling a heavy social pressure as a result. But I’d started now, so I promised myself to continue as best I could, all the way to those fabled stalls near Old Street.

I passed the red brick mansions typical of the area on Chiltern Street until I found the sunny Paddington Street Gardens. The public toilets here are of note for their lovely colourful tiles depicting local scenes, for which they have won awards. Given this, I was expecting something more accommodating, but I found the gents to be very cold, smelly, and dysfunctional in parts. Some of the graffiti in the stalls were fascinating, however. Geoffrey Fletcher noted in the 1960s that toilet graffiti deserve ‘a book to themselves’ (Fletcher: 1962, p. 53), and these ones, in particular, revealed the crucial queer dimension to London’s public toilets and confounded my preconception that ‘cottaging’ was largely dead. These graffiti do, however, indicate that the terms of the cottage have changed. Where in the nineteenth century and beyond these places were defined by anonymous and fleeting sexual encounters, being essentially a necessity for sex and socialising before decriminalisation in 1967, these graffiti advertise online chat groups (one apparently containing ‘1000+ BENDERS’) which hint at the new digitally organised world of cruising.

Passing the man who’d been standing fixed at the urinal for 5 minutes, I wandered along Marylebone High Street and on to Thayer Street. The sun illuminated the fancy shops and well-dressed people marvellously, but it was devoid of anything for our interests. This clearly hasn’t changed in many years; a humorous guide to London’s public conveniences from the 1930s calls these streets a ‘bad spot to be caught in’ ([Burke]: 1937, p. 19). I did, however, take note of Hinde Street Methodist Church, which gently teased me by reminding me of the walk’s goal.

Nearing Oxford Street, I turned into St Christopher’s Place. Once something of a slum, Barrets Court (as it was then called) was redeveloped by Octavia Hill in the 1870s, and since the 1960s has been transformed into an upmarket shopping district. There was a lovely old leafy convenience here, but it was closed. It seems that the ideals of public provision here have strayed quite considerably from Hill’s vision. I then walked down Gee’s Court to Oxford Street itself. Just east of Gee’s Court there was once another small passageway called Stratford Place Mews, where the Pre-Raphaelite painter Simeon Solomon was arrested at a urinal in 1873 for attempting ‘to commit the abominable crime of buggery’. We can see Solomon as the first in a long line of celebrity public toilet scandals, from John Gielgud, to Joe Meek, to George Michael, each of which has indelibly shaped popular perceptions towards public lavatories since. Solomon’s urinal has long since disappeared into a void between an H&M and a Forever 21.

At this stage, I made a bit of a detour. I carried on east along Oxford Street, turning up to Cavendish Square and past Langham Place. The walk had been characterised by a very well-to-do atmosphere up until this point, but this surely reached its height as I crept towards Fitzrovia. I’d come to see a good example of the current trend for renovating old conveniences into bars and cafes. This was the Attendant on Foley Street, a charmingly renovated nineteenth-century public toilet. Although renovation is minimal, maintaining rusted cisterns and chipped tiles, I did learn from the man there that the porcelain urinals replace the original wood ones. I sat at them for a very nice coffee and a coconut brownie while Wham! played on the speakers.

Restored with caffeine and sugar, I headed south down Wells Street and into the heart of Soho. This was the first great mood shift of the walk, as a decidedly more cluttered and noisy leisure succeeded the quiet confidence of Marylebone and Fitzrovia. I passed by the public toilets on Broadwick Street, which is one of the few old underground ones still in use free of charge. I had only really been tempted here by one Reddit user’s assurance that ‘shit gets really, really weird in there’, but I couldn’t detect much of this. Admittedly I didn’t stay long, but I suppose there was a certain leisurely atmosphere down there which belied its unpleasant size and acrid stench.

I curved eastwards past Trafalgar Square and onto the Strand, where I passed the CellarDoor, a popular club that was once a public toilet. I also saw a couple of closed conveniences outside St Clement Danes, before turning north up Bell Yard and to the wonderful cast-iron Victorian urinal at Star Yard. These sorts of urinals were once ubiquitous, as a glance at any nineteenth-century map of London will attest, yet this is one of the few remaining examples. I carried on up Chancery Lane to High Holborn, where one of London’s most fondly remembered toilets once existed, mainly because of the (surprisingly true) tale of an attendant who kept goldfish in the distinctive water tanks. In the film version of The London Nobody Knows, James Mason calls this lavatory ‘an outstanding survival of Victorian London’. It was destroyed sometime in the 1980s. This is the story of most of these old places… closure, disuse, re-appropriation, and destruction.

I then embarked on a rather long stretch eastwards along Charterhouse Street and into Farringdon and Clerkenwell. Amusingly, the coffee I had was making everything a bit urgent, but I managed to control myself enough to stop and have a look at Passing Alley just off St John’s Street. This was originally called ‘Pissing Alley’ until the late eighteenth century, so for whatever reason, it must have been associated with urination at some time. This got me thinking about the politics of public toilets; I thought back to all the stinking alleyways around Trafalgar Square, which are the only resource for the thousands of homeless people in London.

Walking along Old Street was certainly another ‘bad spot’, but I was kept walking by the promise of my next and final stop. Turning south on to the City Road, I found it… Wesley’s Chapel! Built in 1778, the movement’s founder John Wesley moved his congregation to this purpose-built chapel after years of preaching in a converted cannon foundry at Moorfields. Crucially for us, a lavatory was built on the south side of the chapel in 1899, and the gents have remained largely unchanged since then. I felt such relief to be there. I was finally somewhere clean, free, and which exuded a sense of these once common mainstays of old London. As I collapsed onto the bench outside, I was left thinking about the ways in which public provision of public toilets rose, evolved, and declined. Most of the public toilets I visited were built in the late nineteenth century… one can’t imagine such a huge project being undertaken now. Regardless, these old toilets will carry their strange stories for as long as they remain.

All photographs were taken by the author.

Bibliography

Fletcher, Geoffrey, The London Nobody Knows (London: Hutchinson, 1962)

2 thoughts on “Commit No Nuisance: a walk through the history of London’s public toilets”